Section – 112. Birth during marriage, conclusive proof of legitimacy

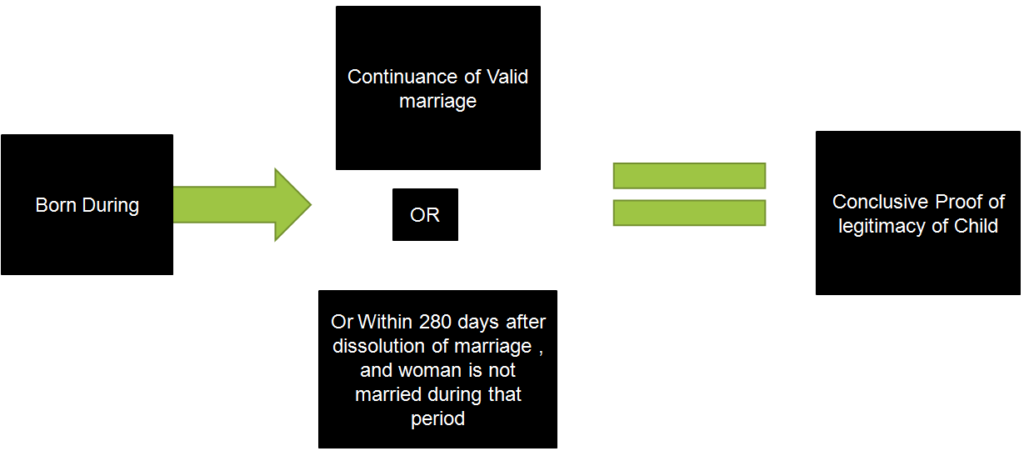

The fact that any person was born during the continuance of a valid marriage between his mother and man, or within two hundred and eighty days after its dissolution, the mother remaining unmarried, shall be conclusive proof that he is the legitimate son of that man, unless it can be shown that the parties to the parties to the marriage had no access to each other at any time when he could have been begotten.

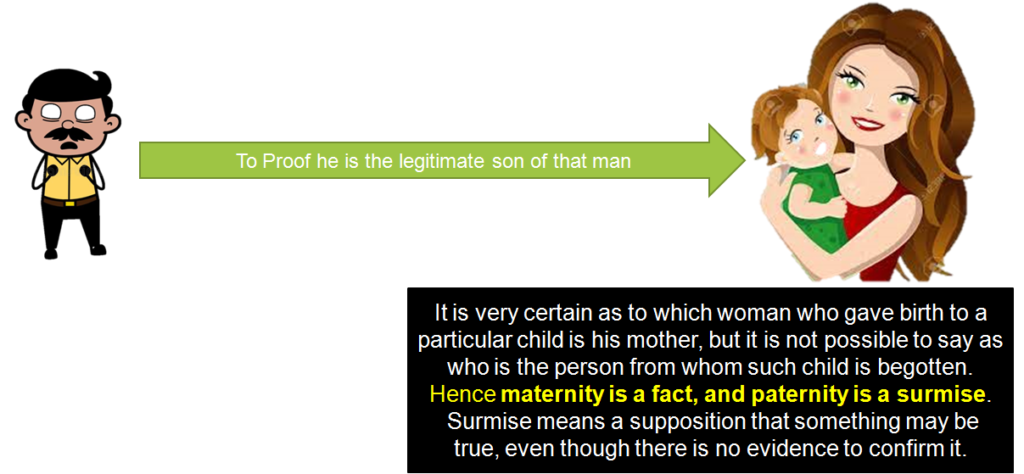

The legal presumption under this section is similar to that of the Latin Maxim, ‘pater est quem muptice demonstrat‘, meaning thereby, ‘he is the father whom the marriage indicates

When we look into the reasoning behind this notion, the only reason which comes up, is that it is undesirable to enquire into the paternity of child whose mother and her husband, had between them, a subsisting marital status and had access to each other.

The objective of the section was to protect the child born, from the social stigma of being illegitimate and to prevent the loss of legal rights, the child would have. The legislative intent of the provision is to protect the rights and interests of the child and to ensure that the child does not become the sufferer.

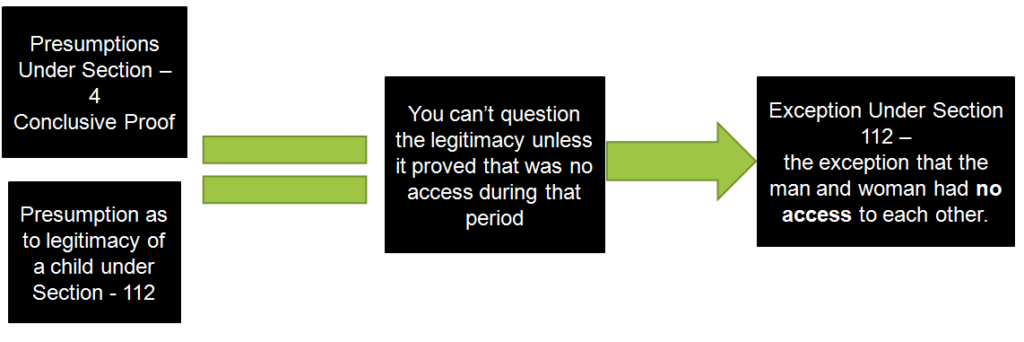

The law presumes strongly in the favor of the legitimacy of the off-spring. The husband who is strongly disputing the point of legitimacy of the child, can only rebut on the issue of ‘access’ and ‘no-access’, otherwise the legitimacy,

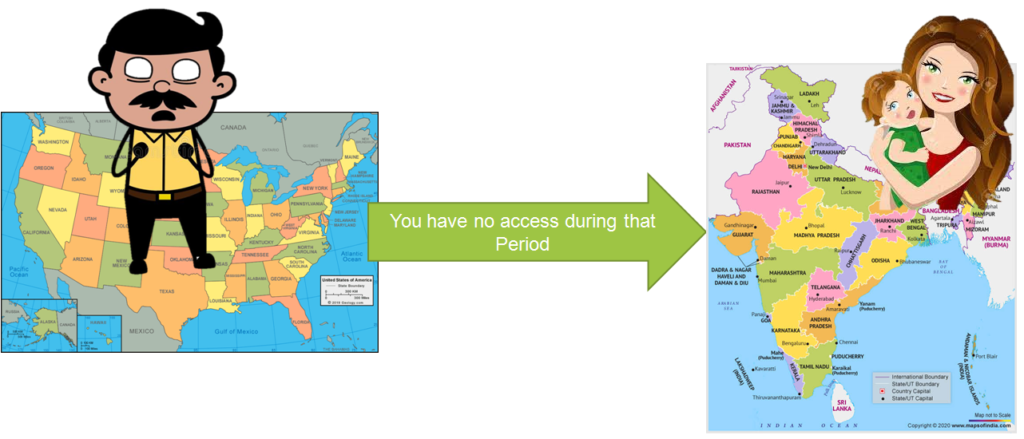

Sec.112 mentions only one particular exception to the presumption of legitimacy i.e. non access of the parties at the time when the child could have been begotten, however if it shown that the circumstance of their access were such as to render it highly improbable that a sexual intercourse took place between them, the presumption as to legitimacy could be rebutted.

In the case of Sham Lal v. Sanjeev Kumar

It is undesirable to enquire about paternity of a child whose parents “have access” to each other or were in continuance marriage with each other. Section 112 of the Evidence Act, 1872 upholds public interest, public morality and public policy. The section is based on well-settled principle of law “odiosa et inhonesta non sunt in lege praesumenda” (nothing odious or dishonorable will be presumed by the law). Section 112 reproduces the rule of English Law which states that it is undesirable to enquire about the paternity of a child when the mother is a married woman and the husband had access to her. The law presumes against vice and immorality. In a civilized society, it is imperative to presume about the legitimacy of a child born during continuation of a valid marriage and whose parents had “access” to each other.

DNA is a powerful tool used commonly for parental testing and forensic testing, which is highly accurate with chances of error being one in one billion. nspite of repeated legal challenges, mainly in the USA, no two persons other then identical twins, have been found to have identical DNA profiles, the possible number of presumptions far exceeding the population of the world.

DNA Tests are conclusive evidence that is admissible under the Indian Legal System to ascertain paternity. The introduction of DNA technology has faced a lot of criticism and it has been mentioned before about it being violative to Article 21 (Right to Privacy) and Article 20(3) (Right against Self-Incrimination) of the Indian Constitution.

In the landmark judgement in the case of Nandlal Wasudeo Badwaik vs Lata Nandlal Badwaik & Anr on 6 January, 2014 , Supreme Court held that where there is a conflict between the contrary scientific evidence and Sec. 112, scientific evidence would prevail

ARTICLE 21– RIGHT TO PRIVACY

Govind Singh v. State of Madhya Pradesh[6]

In this case, the Supreme Court held that a fundamental right must be subject to restriction on the basis of compelling public interest. Thus, Right to Life and Liberty, which includes Privacy, is not absolute. And it is on this basis that the constitutionality of the laws affecting Right to Life and Personal Liberty are upheld by the Supreme Court which includes medical examination

Sharda v. Dharmpal[7]

In this case the court held that (a) A matrimonial court has the power to ask a person to submit to the medical test reports and this order of the Court will not violate a person’s Right to Personal Liberty that comes under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution further it said that the Court must exercise this power only if the applicant has a strong prima facie case and there is sufficient proof before the Court. The Court also stated that if the respondent does not submit himself for the conduction of medical examination, despite the order of the Court. The court will be entitled to draw an adverse inference against him.

Thus, the Court has the authority to direct a person to undergo medical tests. However, according to section 112 of the Act, the Court can only give such orders if non-access is proved.

ARTICLE 20(3) – RIGHT AGAINST SELF-INCRIMINATION

State of Bombay v. Kathi Kalu Oghad[8]

In the following case it was held that “Self-Incrimination means conveying information based upon personal knowledge of the person giving the information and it cannot include the mechanical process of producing documents in court as right against self-incrimination which do not contain any statement of the accused based on his personal knowledge”. Since medical tests which involve giving blood do not involve any exchange of ‘personal’ knowledge and are a mechanical process, they do not violate Article 20(3) unless compulsion was used in obtaining.

No comment